On My Writing, Rhoda Rabinowitz Green

The large number of characters who people my books and stories — provide a context — is a natural outcome, I believe, of having grown up in a small town neighbourhood, surrounded by a close-knit family of nine maternal aunts, uncles, their spouses, many many cousins, and a continuous flow of magicians, acrobats, comedians, tap dancers and pit musicians who played the movie-vaudeville house where my father worked as a projectionist/spotlight operator. My first book, Slowly I Turn, a bildungsroman, and the second, a romantic comedy, Moon Over Mandalay, both number a cast of characters worthy of a Russian novel. It was the early years spent in Bloomington as a student at the university and teaching in rural southern Indiana that provided, decades later, the characters, plot and setting for Moon Over Mandalay (BuskerBooks, Toronto, 2008).

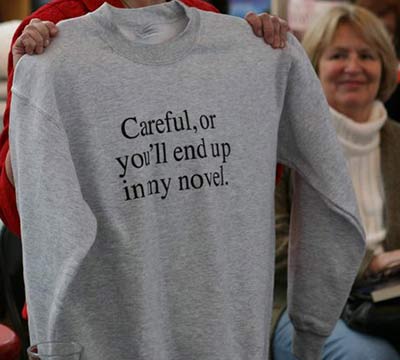

Every writer has stories to tell, but some stories nag at you and won't go away. They are the ones that get written. All of my stories came to me with very strong, visual images, sometimes with remembering a striking snippet of dialogue, many times with two or more ideas or events that seem to demand that they come together. At the beginning of the writing process I have no idea as to how or why they should be related. I have only a very strong conviction that, in some way, they are meant to be together. One constant theme in my writing is music.

If the content of a story does not revolve around a theme about music (or a musician), it invariably coaxes the reader to recall its power and poetry. Writing and music share the same elements: structure or form; arc, phrase, balance, rhythm; pace, flow, sound, tone or timbre, repetition; likeness and difference, variation, consonance and dissonance, tension and response, lyricism, exposition, development, denouement, crescendo, diminuendo, climax, clarity, voice and economy. Every new creative endeavour I have undertaken has been informed by transferring what I know about music.

I once took part in an exercise at an education workshop to demonstrate right brain/left brain function and its implications for teaching and learning. Most, if not all in the class found they were right or left. I was "and." The left, language side, fought for primacy from high school Quill and Quire days and love of languages to the time when it claimed my full attention upon our family's move to Toronto in 1968. On the other hand — I should say "side" — as early as five I knew I wanted to be a pianist. A "right brainer." I have been juggling both right and left sides to the present day.